AiW Guest Sarah Smit

Earlier this year a group of academics, writers and literary producers came together in Cape Town for a workshop convened by Chris Ouma and Madhu Krishnan exploring ‘Small Magazines, Black Archives and Personal Histories’. This piece engages with three separate conversations that formed part of this workshop, each of which loosely responded to the need to attend to ‘unofficial’ sources of affiliation on the Continent and put into conversation experts on and contributors to alternative institutions of contemporary literary and cultural production.

The workshop opened with a conversation between Stacy Hardy, Bongani Kona and Billy Kahora which took place at the Chimurenga office on Long Street. Their collaborative work at Chimurenga and Kwani? prompted a reflection on the modes of solidarity essential to the maintenance of pan-African creative networks. These small magazines and their various incarnations seek out intellectual communities that exist outside of geographically and institutionally determined spaces. Research methods are thus reliant on anecdotal knowledge passed through intimate connections, rather than through sanctioned cultural spheres. A compelling proposal that came out of the discussion suggested that these contemporary manifestations of the ‘literary’ journal are concerned with imagining a future reading community – anticipating an eternally changing relation to cultural production on the Continent.

The discussion that followed with Kelwyn Sole, an editor of the literary magazine Donga, and Zebulon Dread, South Africa’s self-styled culture terrorist, in conversation with Khwezi Mkhize (UCT), challenged the persistent intellectualisation of the discourse surrounding small magazines. Sole traced the history of literary journals in South Africa and pointed out that the cultural capital of a magazine like Staffrider is linked to a tacit rejection of the Marxist aesthetics in earlier journals and a newfound investment in the ‘literary’ as a political site. Sole questioned the logic of who decides what radical art is or isn’t, considering the institutional memory some magazines manage to acquire above others within the political consciousness of publication.

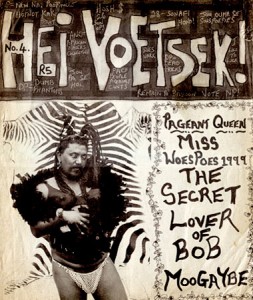

Dread, in his current incarnation as The Black Guru, Swami Sitarama Dasa, provoked his audience by affirming the political urgency of countercultural production against the current dispensation. Basically satirising the polite intellectual gathering at Chimurenga that afternoon, the founder of Hei Voetsek! repudiated the comfortable position from which cultural journals operate in the Rainbow Nation. Dread’s performance, and his recollection of his work single-handedly putting together Hei Voetsek!, attested to the radical impact of free expression amidst the politics of respectability in the New South Africa. According to the artist, the political diatribes in the pages of Hei Voetsek! sought to reject the hierarchies of value created by the publishing industry – sardonically represented in Dread’s obstinate terrorism of the conservative Klein Karoo National Arts Festival.

Dread, in his current incarnation as The Black Guru, Swami Sitarama Dasa, provoked his audience by affirming the political urgency of countercultural production against the current dispensation. Basically satirising the polite intellectual gathering at Chimurenga that afternoon, the founder of Hei Voetsek! repudiated the comfortable position from which cultural journals operate in the Rainbow Nation. Dread’s performance, and his recollection of his work single-handedly putting together Hei Voetsek!, attested to the radical impact of free expression amidst the politics of respectability in the New South Africa. According to the artist, the political diatribes in the pages of Hei Voetsek! sought to reject the hierarchies of value created by the publishing industry – sardonically represented in Dread’s obstinate terrorism of the conservative Klein Karoo National Arts Festival.

The next day, in the comfortable yet awkward setting of the Kipling Room in the University of Cape Town’s Special Collections Library, the agenda was to address literary festivals, prizes and the politics of cultural production. Doseline Kiguru, a fellow at the British Institute in Eastern Africa in Nairobi, opened the discussion with a reflection on her own work around this subject and a compelling engagement with James English’s The Economy of Prestige (2005). Kiguru questioned the role of African writers in sustaining traditions of patronage within contemporary literary culture on the Continent, questioning what it has come to mean to be one of ‘Chimamanda’s boys’ in the context of the Nigerian literary scene. Kiguru also probed one of her fellow discussants, Bwesigye Bwa Mwesigire, to flesh out the politics of the Writivism festival in light of the critique levelled by English. Bwa Mwesigire, founder of the Kampala-based Centre for Cultural Excellence, followed up Kiguru’s challenge with a strangely moving letter to Writivism, recounting its birth and the struggles that followed. The letter opened up about the practicalities of creating an alternative literary public and the ways in which this project sometimes has to acknowledge its replication of conventional dynamics between writers and their readers.

Thando Mgqolozana, writer and founder of the Abantu Book Festival, joined the conversation by explicitly rejecting the prolonged scholarly investment in appraising the significance of literary prizes, especially the Caine Prize for African Writing, in the shaping of a contemporary readership. Mgqolozana reiterated the need to conceive of future modes of affiliation by engaging alternative cultural spheres. To some extent, the room at this point couldn’t help but feel out of touch with these imagined readers, Bwa Mwesigire even wondering out loud if these readers had even heard of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie.

The discussion inevitably ended up reflecting on the power of the African writer in cultivating a readership beyond the critical influence of Western literary institutions. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s summoning of a loyal working-class following became the subject of the session’s most heated debate – the writer’s myth-making tendencies provoking scepticism from some. Others insisted on wa Thiong’o’s obligation to practice his persistent emphasis on language more meaningfully by establishing literary institutions that make space for writing in African languages.

The talk that wa Thiong’o recently delivered at the University of Cape Town maintained that the question of language must be central to the writer’s quest for relevance on the Continent. The event was summarily disrupted by students from the Pan Africanist Student Movement of Azania, who called for wa Thiong’o to ask white members of the audience to leave. Wa Thiong’o responded by invoking his personal experiences of political organisation in Kenya, suggesting the need build coalitions through a shared ideological base – “The key word here is the ‘base’. From the base we can make contact, we can make alliances. Because not everybody thinks alike, not all of your peers are of one mind. And not all Africans, by virtue of being African, are for revolutionary change.”

Wa Thiong’o’s appeal to negotiated modes of solidarity affirms the need for critical intervention on the field of cultural production. In seeking out alternative literary histories, scholars and practitioners are able to examine the dimensions of dissidence for future reading communities. The workshop itself responded to the political urgency of the contemporary moment, while reflecting on those instants of complicity that sometimes seem unavoidable when operating from within the institution.

Sarah Smit has a master’s degree in English Literature from the University of Cape Town. She is interested in the literature of the contemporary black diaspora and its intersection with queer aesthetics of solidarity. Her recent work considers the connections between South African literary history and literature from the rest of the Continent.

Sarah Smit has a master’s degree in English Literature from the University of Cape Town. She is interested in the literature of the contemporary black diaspora and its intersection with queer aesthetics of solidarity. Her recent work considers the connections between South African literary history and literature from the rest of the Continent.

This is the first in a new series of articles publishing over the next six months on Africa in Words, that come out of conversations between a new interdisciplinary network of researchers and literary producers examining the circulation and production of small magazines in Sub-Sahran Africa. This AHRC Research Network, ‘Small Magazines, Literary Networks and Self-Fashioning in Africa and its Diasporas’ is convened by Dr Madhu Krishnan (University of Bristol) and Dr Chris Ouma (University of Cape Town) and this year has hosted workshops in Cape Town (April 2017) and Kampala (August 2017) to explore the relationship between small magazines and the construction of affiliation, identity and civic participation. New research coming out of this network will be showcased at a conference hosted at University of Bristol in January 2018.

Categories: And Other Words...

Reviews: ‘The porousness of cultural boundaries’ — Thoughts on the publication of Karin Barber’s A History African Popular Culture (2018)

Reviews: ‘The porousness of cultural boundaries’ — Thoughts on the publication of Karin Barber’s A History African Popular Culture (2018)  In other Words… AiW news & wrap for September

In other Words… AiW news & wrap for September

join the discussion: