Emmanuel Iduma co-founded the Nigerian literary magazine Saraba in 2009. The magazine, now in its 14th issue, aims to ‘create unending voices by publishing the finest emerging writers’. Each issue is published in PDF and ‘themed’ – with recent editions focusing on Sex, Justice, Africa and Art.

Emmanuel Iduma co-founded the Nigerian literary magazine Saraba in 2009. The magazine, now in its 14th issue, aims to ‘create unending voices by publishing the finest emerging writers’. Each issue is published in PDF and ‘themed’ – with recent editions focusing on Sex, Justice, Africa and Art.

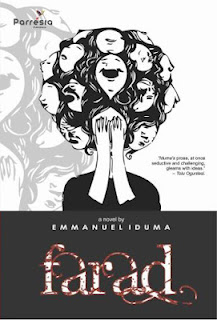

Iduma’s first novel Farad was published by Parresia in 2012 and has been described by Victor Ehikhamenor as capturing ‘a fractured complex co-existence of various characters that live on the edge of combustible times’ and providing an ‘immediate history’. He was longlisted for the Kwani? Manuscript Project for Becoming God and you can read some of his writing here.

Iduma is involved in a large number of creative projects including Saraba, Invisible Borders, curating TEDxIfe, 3Bute and Gambit – a series of interviews with contemporary African writers. This is an extract from our conversation last May at LitCaf in Yaba, Lagos and captures a snapshot of Iduma’s thinking about writing, Saraba, Farad and Gambit.

I was in university, in my 4th year – I studied Law in Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife. I had organised a workshop for writers in the university and met Dami Ajayi – he was the first person that applied for the workshop. We became friends and he started coming to my house every weekend and we’d discuss literature, discuss the books we were reading, discuss our writing – he was writing mostly poetry and I was writing short stories. This was in late 2008. So we usually sent out our material and got rejected – the usual thing! And then one day we found a really really cool magazine online called The Writer’s Beat. I don’t know what has happened to it. Anyway it wasn’t Nigerian, it was mostly American content, and so we said to ourselves ‘let’s do something for Nigeria’.

I was in university, in my 4th year – I studied Law in Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife. I had organised a workshop for writers in the university and met Dami Ajayi – he was the first person that applied for the workshop. We became friends and he started coming to my house every weekend and we’d discuss literature, discuss the books we were reading, discuss our writing – he was writing mostly poetry and I was writing short stories. This was in late 2008. So we usually sent out our material and got rejected – the usual thing! And then one day we found a really really cool magazine online called The Writer’s Beat. I don’t know what has happened to it. Anyway it wasn’t Nigerian, it was mostly American content, and so we said to ourselves ‘let’s do something for Nigeria’.

To be frank with you the original intention was to publish ourselves. We said ‘okay let’s publish ourselves, let’s be able to control the kind of stuff we get out.’ And so that was the beginning of everything now that has come to be. We put out a call for submissions and incidentally one of friends, Jumoke Verissimo, was freelancing for a popular Nigerian newspaper Guardian. She put out our call and it was really popular. We got hundreds of submissions and she was the guest editor. So that was the first issue in February 2009.

Our focus has always been to publish young writers who have never been published before. We felt there was writing out there with a kind of context that American literary journals or British literary journals did not want, I mean it wouldn’t resonate with them. And so our focus was to publish writing that only a Nigerian or an African magazine could find interest in.

Our focus has always been to publish young writers who have never been published before. We felt there was writing out there with a kind of context that American literary journals or British literary journals did not want, I mean it wouldn’t resonate with them. And so our focus was to publish writing that only a Nigerian or an African magazine could find interest in.

Basically what has happened is that Saraba has grown into what we didn’t expect. We didn’t even have expectations to be frank with you! We were just young university students who just felt we could do this. After the first issue, it became clear that we were doing something new and that nobody was doing this in the country. There were no websites and even if there were websites, they were not as solid as we would expect. So Saraba was really well received and it still is well received today. We can now say we are among the best literary journals coming out of Nigeria.

There is something also about publishing in PDF that makes it really really cool; people have something to take away from the web. From the start we said we are going to always publish PDFs and then eventually go to a print journal. Our plan is that by next year we should have our first print journal.

Lastly I should say that Saraba has grown from our personal funds – of course there are no places to apply for grants. To host the website is not too expensive and nobody is being paid. From the start we’ve always had volunteers – myself, Dami Ajayi and then we had friends who were writers who would come and edit the journal for us. We have a fiction editor, a poetry editor, a non-fiction editor, a managing editor, someone who manages the website. So basically we have a staff of 7 of purely volunteers.

And from the beginning was each issue focused around a particular theme?

Yes, from the beginning we said to ourselves that for each issue we’d pick themes to explore. The whole idea was to find intersections between literature and life, so to speak. Our first issue we had a Family issue. From there we moved to more daring subjects like Sex, Africa, Arts. What Saraba has evolved to now is not just a literary journal; I’d also say it is an arts journal in a way. We have submissions from photographers and we enter into collaboration with digital artists, and because we have a good platform, we are able to do trade-offs or exchanges.

Yes, from the beginning we said to ourselves that for each issue we’d pick themes to explore. The whole idea was to find intersections between literature and life, so to speak. Our first issue we had a Family issue. From there we moved to more daring subjects like Sex, Africa, Arts. What Saraba has evolved to now is not just a literary journal; I’d also say it is an arts journal in a way. We have submissions from photographers and we enter into collaboration with digital artists, and because we have a good platform, we are able to do trade-offs or exchanges.

Our goal now is to become more credible. We recently had an interview with A. Igoni Barrett and I’m going to do one with Chibundo Onuzo. I’d like to do one with Binyavanga Wainaina. So Saraba is also a community for us as writers and a way of tapping into a community of writers.

Can you talk me through the editorial process of putting the magazine together? How much material is commissioned and how much do you get through submissions?

We do both – we have solicited and unsolicited material. The last issue, the Africa issue, we did a lot of commissioning and asked authors who we thought had written something good – ‘can we republish or can you give us new material?’ So we basically did some scouting. For this issue we are saying, ‘right, we want new material only.’ The truth is that when you are doing a magazine of this sort and you begin to grow and have a certain standard, you tend to reject more and more.

Which issues have been your most popular?

Which issues have been your most popular?

The Sex issue. The Niger Delta issue. The Economy issue.

Which other literary magazines do you think are doing exciting things in the same space in Nigeria or Africa more broadly?

In Nigeria, to be frank, I know of probably only one – which is Sentinel. It is actually published by Richard Ali, so there is only a tiny republic – everybody knows each other. It gets me worked up sometimes – who are we are doing this for at the end of the day?

I’m a big big fan of Chimurenga. Probably the biggest fan! And I’m contributing a piece to The Chronic which I’m really excited about.

So Chimurenga, Kwani?, Bakwa Magazine. I met the editor Dzekashu MacViban in Yaoundé last year and he is a really amazing guy.

Who else? There are very few actually. Jungle Jim. I don’t know so much about what is happening in North Africa. That is something that I’m interested in knowing, what is happening in that space. And then also Francophone Africa.

So I want now to move to some questions about your own writing and particularly about your first novel Farad. Could you talk a bit about your motivations for writing Farad and what you were trying to do in the novel?

I’d been writing since forever, you know, since I was a kid. Everybody says that actually, but I’d been always conscious of the fact that I wanted to write. I wanted to get stuff out.

So my motivation was that it was time to get published first and foremost. I had a completed manuscript and I started looking for publishers. I tried agents in the UK, that didn’t work. And then I thought let me try and see if I could self-publish. So I was in touch with this editor, who happens now to be my publisher, and she read it to edit it at a fee for me and she said ‘No! I’m starting this publishing house, I want to publish this’. So I’m like ‘oh okay, I have nothing to lose really!’ If someone wants to put their money into this, is willing to undertake the distribution, it is a first novel – I have no points to prove. It is quite experimental in terms of the plot, so if someone likes this, ‘cool!’ So it was simply the time for it, it was simply opportunity – but of course that had come from a long period of writing and being in the writing community. Something needed to happen to go to the next level, to at least put my foot in the door.

In Farad, I wanted to experiment with the idea of what a narrative is. I felt like the questions I was trying to ask and answer through the book, could be answered in that way and not necessarily by a straightforward narrative. I wanted to take different characters in their own spaces, doing their own things to try to answer those questions. Then again, I didn’t care, I didn’t have a care in the world. I just felt this is how I want to write this story. To be frank with you, a lot of questions I’ve been answering about the book over the last nine months have been things that I thought about after. At that time, I didn’t care about anything else. I was just writing the kind of stories I wanted to write, putting it together the way I thought I wanted to put it together.

So did you have a particular reader in mind that you were writing for?

No and that is quite funny, because people have accused me of so many things after reading the book, for instance that I’m trying to impress. This question is so important because what I’m working on now I have a particular reader in mind and it is an intelligent 7 year old. But then, I didn’t have any single person in mind. If I had any reader, it is probably myself. I’ve had this argument with several people who say you shouldn’t write for yourself. And I say I can’t write for any person except myself. If I can’t convince myself then I have no responsibility to any other person. Eventually, maybe in the second draft when I’m editing, the reader comes into it. But when I’m working, I’m thinking am I being true to the story, the kind of story I want to write, the kind of world I’m creating? That’s basically all that matters to me.

Were you involved in the cover design?

Yes I was definitely! Is it obvious?

The publishers were having difficulties coming up with a design I liked and you know I also design – so I’m like this should not be difficult. I started looking through my collection of all the illustrations I’d collected and I found it. I sent it to the publishers and they liked it, so we contacted the artist. So for me, her illustration represents what I was trying to do in the novel. The fact that the whole plot is centred on unity and diversity, so this is a head with a number of faces – some are laughing, some are sad, some are sleeping. The fact that there are parallel lives, and yet there are some meeting points – so you can find narrative, you can find plot; you have a number of sub-plots and then a single story finally at the end.

Have you been pleased by how Farad has been received?

To be frank with you, I didn’t have any expectations. Who bothers about how a book is received when he is 23? But I’ve been pleased. It is quite humbling in many ways. It has been adopted by two universities, so that makes it quite huge. I get to talk to all these students who ask me all these questions because they have to write examinations. How do you answer?

What I had in mind when the book was coming out, was okay cool, I’m not really interested in winning an award with this book or anything, I just want to get it out there. I just want to begin to take myself seriously as a writer and definitely I feel that way now. And now I have to think about the second book! The second book I hear is the hardest to write and it is really hard. I’ve written less than 10,000 words in 3-4 months. So definitely I’ve been kind of pleased and kind of scared and shocked at the same time. It is now putting me in a place where I have to be careful not to write for anybody. To just keep being that person I was, with the kind of ideas I have at the heart of all my writing when this was not published.

Where have conversations about the novel been taking place?

Of course there have been a lot of reviews – about 10 or so, mostly online. Each time I get one of those reviews I put it on my site, so that at least I can track them.

One of the things I’m happy about is that I’m not just getting reviews or conversations about the book from people that are literary critics or students. For example, friends of mine have read the book and they send me emails and tell me what they think. That for me is perhaps the most amazing thing – these guys are not experts and they don’t want to be. They simply want to appreciate the story for what it is, and you can actually feel that honesty in their responses. A number of people have said ‘ooh I read your book’ and this is what I liked, this is what I didn’t like, this is what I didn’t get. Someone said to me the reason they liked the book is that it had many beautiful sentences, but they didn’t really get the plot. So I said, ‘fine’ – there is something that worked for you and that is all that matters.

Another project I wanted to ask you about is Gambit. Can you tell me a bit about that and how it came about?

In 2011 I was in Khartoum and I had just started blogging for The Mantle. This was a period where I was doing a lot of soul searching and had just left law school; I never wanted to practice law and was wondering what to do with my life. I thought about the fact that I’d been a big big fan of the Paris Review conversations. I’d been a big big fan of Michael Silverblatt’s Book Worm stuff. I’m like ‘okay there is nobody doing this in the African context’ and I thought let me just do it. Let me just have interviews and conversations with writers. My bias was towards emerging writers who didn’t have their first book out. I wrote to Shaun Randol, the editor in chief of Mantle and he said ‘fantastic – let’s do it’ and so I compiled a list of 10 names. From Nigeria it included Abubakar Adam Ibrahim, Ayobami Adebayo, Richard Ali, but also writers from outside the country – Novuyo Rosa Tshuma from Zimbabwe living in South Africa, Abdul Adan – a Somali writer living in the US, Donald Molosi from Botswana, Dango Mkandawire from Malawi. So what I did was basically to read through all their work, not all but everything online, and ask them to send PDFs if they had material that was about to be published or something that really evoked their aesthetics. I read through them and prepared questions as honestly as possible. It was really fascinating because every conversation I got to ask new questions. Often the writers would be saying ‘nobody has ever seen my work in this light, I have to think about this’. One of the best comments was from the first interviewee who told me the interview had even changed the way she looked at her work; that for me was really massive. The editor too commented on the ways in which each interview was different. I think the tendency when going through this kind of process is to ask the same questions, but for Gambit each interview was different and I think that was because I put my heart into it. I really wanted to understand those writers!

In 2011 I was in Khartoum and I had just started blogging for The Mantle. This was a period where I was doing a lot of soul searching and had just left law school; I never wanted to practice law and was wondering what to do with my life. I thought about the fact that I’d been a big big fan of the Paris Review conversations. I’d been a big big fan of Michael Silverblatt’s Book Worm stuff. I’m like ‘okay there is nobody doing this in the African context’ and I thought let me just do it. Let me just have interviews and conversations with writers. My bias was towards emerging writers who didn’t have their first book out. I wrote to Shaun Randol, the editor in chief of Mantle and he said ‘fantastic – let’s do it’ and so I compiled a list of 10 names. From Nigeria it included Abubakar Adam Ibrahim, Ayobami Adebayo, Richard Ali, but also writers from outside the country – Novuyo Rosa Tshuma from Zimbabwe living in South Africa, Abdul Adan – a Somali writer living in the US, Donald Molosi from Botswana, Dango Mkandawire from Malawi. So what I did was basically to read through all their work, not all but everything online, and ask them to send PDFs if they had material that was about to be published or something that really evoked their aesthetics. I read through them and prepared questions as honestly as possible. It was really fascinating because every conversation I got to ask new questions. Often the writers would be saying ‘nobody has ever seen my work in this light, I have to think about this’. One of the best comments was from the first interviewee who told me the interview had even changed the way she looked at her work; that for me was really massive. The editor too commented on the ways in which each interview was different. I think the tendency when going through this kind of process is to ask the same questions, but for Gambit each interview was different and I think that was because I put my heart into it. I really wanted to understand those writers!

Gambit has become really successful and we are planning a book now, collecting together all the interviews with short stories from each of the writers. This is really really different, because often when you get to read short stories from a writer you never really know how they think. So we are putting their short stories side by side with their interviews. That is supposed to be out before the end of the year.

What would you say were the most exciting things currently happening in Nigerian writing and publishing?

This is a big question. First of all brave people like Parrésia. I think I will just be honest with you, because it is so important and dear to my heart that every single opportunity I have to talk about it I want to make sure I’m honest. Nigerian literature is at a very transitional stage. If you look at these photos lining the walls of this book café – Ben Okri, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Teju Cole, Biyi Bandele – you will realise that these writers are based out of this country. And you are like, why? It is a simple thing. It is a game of numbers, because the Nigerian publishing industry has not grown to the level where we can publish a book in 10s of 1000s. So in the UK or the US they have an audience, they have thousands or millions of people who are ready to buy a book if it is pushed enough. So writers like Adichie or Okri become stars, literary stars. But why I think these things are changing is because now there are brave publishers. Because the basic problem is not really that people are not writing. When people talk about the fact that there was a lull – I’m like writers never stopped writing; in the 80s, in the 90s, writers never stopped writing. The only thing that happened was that there were few outlets and this is changing now. This is a transitional stage and a lot of us are going to pay price for that transition, because if you are not a writer who is interested in living in the West for instance and trying to get your way into those publishers, you might have to pay the price.

What I’ve always said is that it is very important for us to highlight that there is a marked difference between the writing of Nigerians published abroad and the writing of Nigerians published in Nigeria – not in terms of the content but in terms of, should I say, the politics of the presentation. In terms of who is publishing, the capacity of the publishers, the distribution channels – there is a marked difference. So it is important for us not to underrate writers who are based here. Coming to your question directly, I think what is happening is that we are transitioning to a place where home-based literature can become reckoned with in the world. And that is happening because people are making brave decisions. People are saying, ‘we don’t have any funds but we are going to get a loan from the bank and make publishing work in Nigeria’. People are saying ‘we are going to start book festivals in Nigeria’. People are saying ’we are going to adapt books for mobile’. Really exciting stuff that is happening because people now believe that things can work despite infrastructural challenges, despite the fact that nobody cares about the publishing industry and paper tariffs are high, you know. It is going to be slow, but I think it is going to be steady and eventually get somewhere. I just don’t know where it is going to get to!

You can follow the work of Saraba and Emmanuel Iduma on Twitter at @Sarabamag and @emmaiduma.

Africa in Words will be showcasing and sharing extracts from Saraba’s latest Art issue next week.

Categories: Conversations with - interview, dialogue, Q&A

Words on…Past & Present: The International Black Speculative Writing Festival (London & Remote)

Words on…Past & Present: The International Black Speculative Writing Festival (London & Remote)  Q&A: Publishing roundtable – #ReadingAfricaWeek

Q&A: Publishing roundtable – #ReadingAfricaWeek  Q&A: Words on… e-Kitabu – the Rights Café, Nairobi International Book Fair

Q&A: Words on… e-Kitabu – the Rights Café, Nairobi International Book Fair  Q&A: Words on… Ambassadors at the Rights Café, Nairobi International Book Fair

Q&A: Words on… Ambassadors at the Rights Café, Nairobi International Book Fair

Reblogged this on On Writing, Music, Love and commented:

Here is a fine interview granted by my friend and co-publisher, Mr Emmanuel Iduma, a legal luminary who has abadoned the wig and instead wades through the tarmac of creative writing with his pen.